Quick question, give me a random number between 1 and 10. What did you pick? two? four? possible, but very unlikely. Most likely you picked seven. Another one… Give me a random color. Did you pick green? Or maybe chartreuse? Again, possible, but unlikely. You most likely said blue. This is called the “blue-seven phenomenon” and it exists because humans are horrible at randomness.

Nature is better at randomness. In nature, we see patterns, like the repeating shapes of leaves or the shells of snails. But nature also has randomness, the movement of particles in the atmosphere, the location of each freckle on your skin. In nature, randomness is pretty common.

Randomness in generative art

This gets us to generative art. In generative art you want your code to output something that follows an algorithm, which is not necessarily random. But you also want the output to be natural, which is random.

To solve this problem, you need to take a strict algorithm and add in randomness in controlled places. Let’s start with a strict algorithm. The example codes are all built in Processing.

void setup() {

size(500, 100);

}

void draw() {

for (int x = 0; x < width; x++) {

for (int y = 0; y < height; y++) {

float red = map(x, 0, width, 0, 255);

float green = map(y, 0, height, 255, 0);

float blue = map(x+y, 0, width + height, 255, 0);

stroke(color(red, green, blue));

point(x, y);

}

}

noLoop();

}

This generates this gradient:

It generates that precise gradient each and every time I run the code. Let’s add some randomness.

Random numbers

We change our code slightly to include some random numbers.

void setup() {

size(500, 100);

}

void draw() {

for (int x = 0; x < width; x++) {

for (int y = 0; y < height; y++) {

float red = map(random(x), 0, width, 0, 255);

float green = map(random(y), 0, height, 255, 0);

float blue = map(random(x+y), 0, width + height, 255, 0);

stroke(color(red, green, blue));

point(x, y);

}

}

noLoop();

}

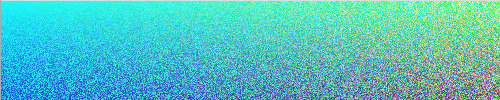

I’ve changed the code to take a random number when determining a point’s color. It’s a slight change, but the output is very different. Below is an example of what the output could look like.

Each time I run the code now, it looks slightly different. The gradient now looks grainy because for each point a random number is generated that influences the color.

The random function generates a semi-random number where each number is equally likely to come up. Think of it like rolling a single die. On a single six-sided die, each number is equally likely to come up. I say semi-random because programming languages use an algorithm to generate random numbers. For us humans, they seem very random. But, if you look closely at the numbers these algorithms generate, you can find a pattern.

In generative art, using random numbers means you are happy with each option coming up equally often. For instance, if you have an array of colors to choose from and you want each color to appear about as often in your work as the other colors, you use random.

In a lot of cases, though, you want more control over the random numbers.

Normal distributions

This may sound odd, wanting to exert some kind of control over random numbers. Board games do this a lot. In a game of Catan, this is very visible. You roll two dice, generating a random number between 2 and 12. But because there is only one way to roll a two, this number only comes up once in a while. A seven, however, can appear on several possible rolls. This means a seven is more common. Catan uses this fact to make some areas very strong and others very weak.

This is called a normal distribution or a Gaussian distribution. Numbers closer to the mean are more likely than numbers at the edges.

void setup() {

size(500, 100);

}

void draw() {

for (int x = 0; x < width; x++) {

for (int y = 0; y < height; y++) {

float red = map(randomGaussian() * x, -width, width, 0, 255);

float green = map(randomGaussian() * y, -height, height, 255, 0);

float blue = map(randomGaussian() * (x+y), -(width + height), width + height, 255, 0);

stroke(color(red, green, blue));

point(x, y);

}

}

noLoop();

}

Our code is changed to use randomGaussian. This function returns a number with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Technically, the function can return any number, but for our purposes, we’re just going to assume they’re mostly going to be between -1 and 1.

The gradient is less visible now because most numbers are going to be close to zero. Multiplying by our current x or y position only has a mild influence on this.

Normal distributions are very useful in generative art since they are predictable, yet random. Anytime you want to randomize numbers without moving too far away from the original number, normal distributions are the solution.

Noise

There is another type of control you could put on random numbers. In our previous two types of random numbers, each number was independent. If you generate a set of random numbers, none of the generated numbers would be related to the other numbers in the set in any way. Noise algorithms, however, generate numbers that do have a relationship to the other numbers in the set.

To get a better understanding of what’s happening, I’ve updated our little example algorithm to use noise. And to truly appreciate what is going on, I’ve turned the color into a greyscale.

void setup() {

size(500, 100);

}

void draw() {

for (int x = 0; x < width; x++) {

for (int y = 0; y < height; y++) {

float xOff = x;

float yOff = map(y, 0, height, 0, 500);

float red = noise(xOff / 500, yOff / 500) * 255;

float green = noise(xOff / 500, yOff / 500) * 255;

float blue = noise(xOff / 500, yOff / 500) * 255;

stroke(red, green, blue);

point(x, y);

}

}

noLoop();

}

First, note that noise can have multiple dimensions. In our case, we use two-dimensional noise. This means that when we pick a number out of our noise algorithm, it is going to relate to the numbers to the left and right of it, but also to the numbers above and below.

Also, note that we are picking numbers out of a predefined set. That set changes every time we run the code. But, during the execution of our code, that set is not going to change. So calling noise three times in a row for the same x and y-position will result in the same number. In our example code, this means that red, green, and blue are always going to be the same number. The result is the image below.

As you can see, the generated numbers don’t jump from highs to lows as normal random numbers would. Instead, the numbers move smoothly from lows to highs. This creates, in our example, an almost cloud-like effect.

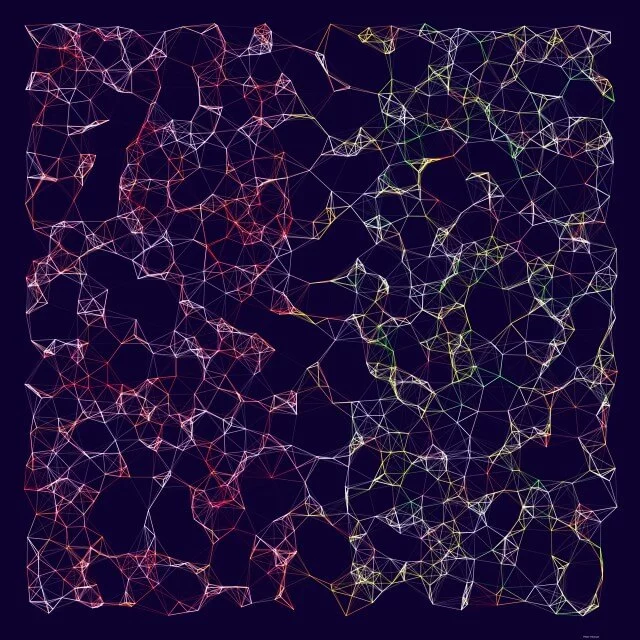

Noise algorithms are often found in generative art in the form of flow fields. Where the number generated for a location is converted into a vector (or direction/force). This can be used, for instance, to make particles move across the screen in a natural-looking way. I’ve used this myself in several drawings: Forest for the Trees, Down by the River, and Coral 1.